Collaborative project and performance | Montréal, Val de Marne

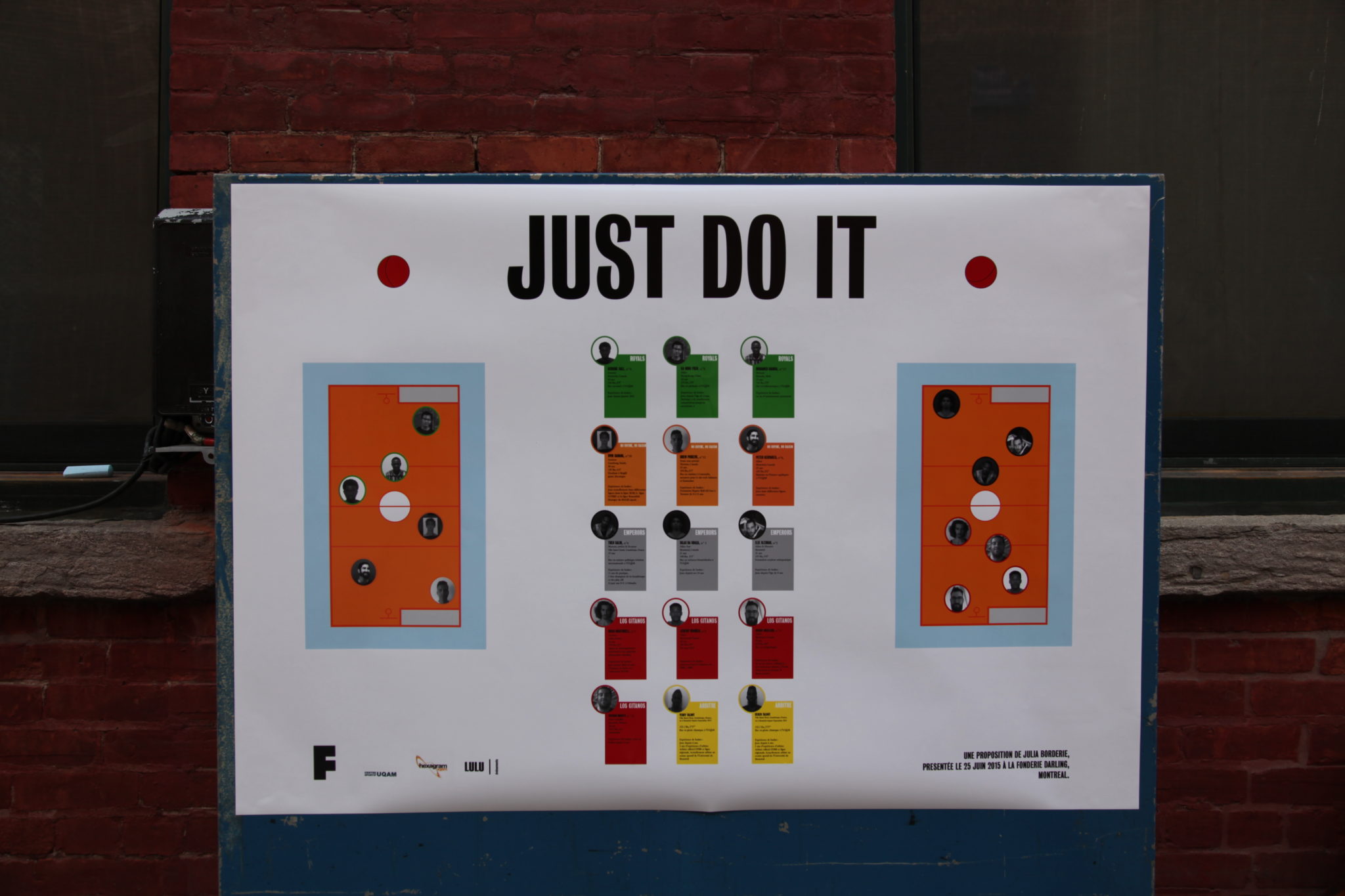

JUST DO IT

2015 – Collaborative project and performance | Darling Foundry, Montréal | 130″

In collaboration with the players Maude Bernier-Chabot D’amour, Benoit Meilleur, Ka Ming Yuen, Hugo Martorell, Dvir Cahana, Théo Salin, Mohamed Diarra, Peter Keryakes, Silas da graçia, Drew Picklyk, Serigne sall, Elie Sleiman, Sylvain Martet, Jeremy Noumen ; les arbitres Kenzo, Yency Talbot ainsi que le commentateur Pascal Jobin.

Just do it is a research based performance that is a collaboration between a basketball team and artists. The game of basketball is used as a template to explore a context of place, from the microcosm of the court to the vastness of a city.

Just do it is a performance which meets the challenge of exploring a common space between sport and the visual art discipline. The project’s goal is to question the representation of pre-established social contexts within both these worlds. This is a performance that works in close collaboration with a basketball team to explore forms of communication between the two disciplines. In a continuous gestural dialogue, this serves to destabilize and re-evaluate their respective functions. Thus transforming the game into a new model based on adaptation.The game’s structure is considered as a score, as for music or dance, the aspects of which are free to be altered, broken-down and modified each time it is played.

The purpose of this collaboration between artist and athlete is to define new gestures that will modify certain laws of the game. The aim is to shift basketballs inherent operating ideas/issues while nurturing the necessary tensions that provide the players with the motivation to win. In these new terms, strategy, collaboration and chance are the motivating factors in understanding other ways of considering success.

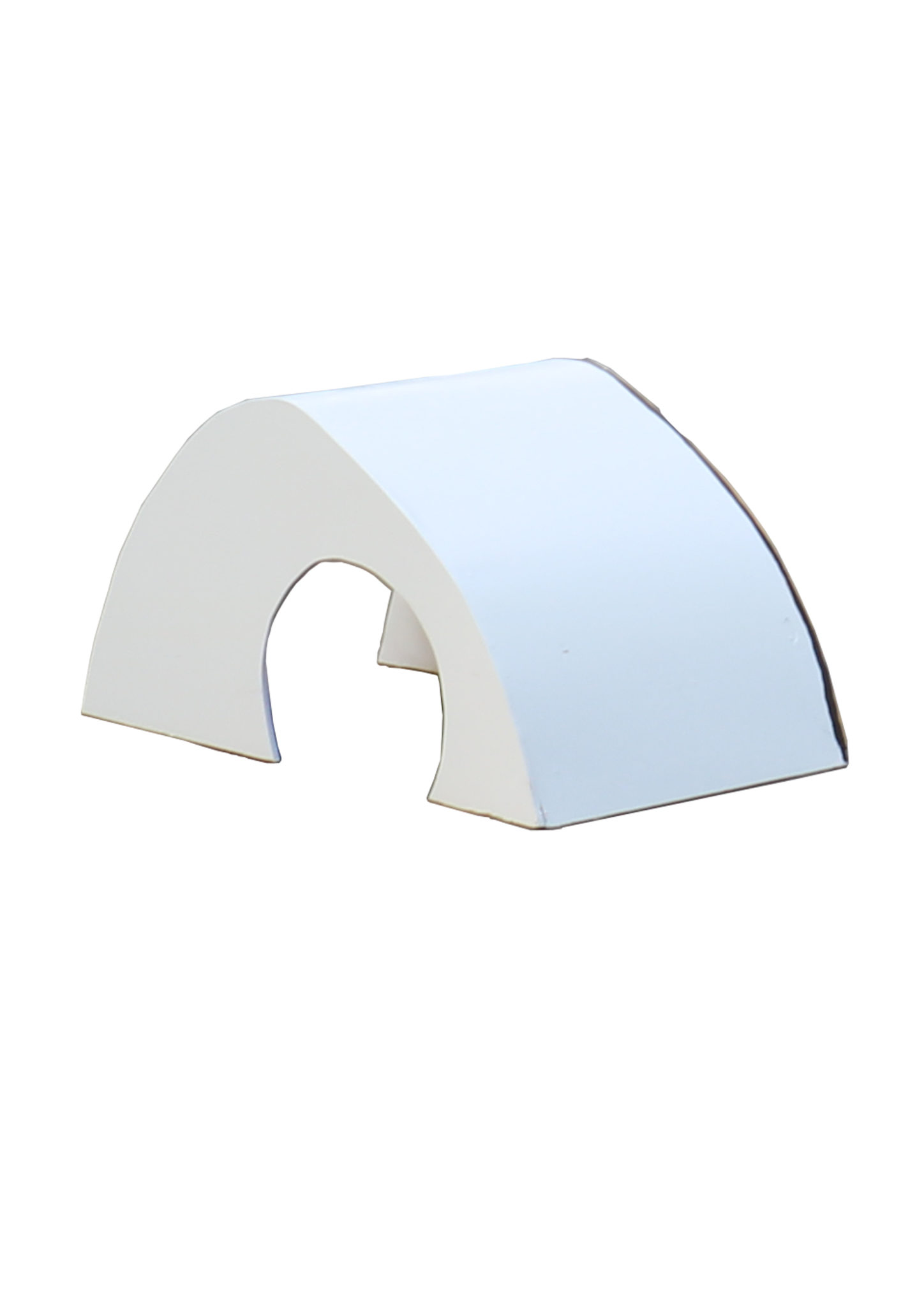

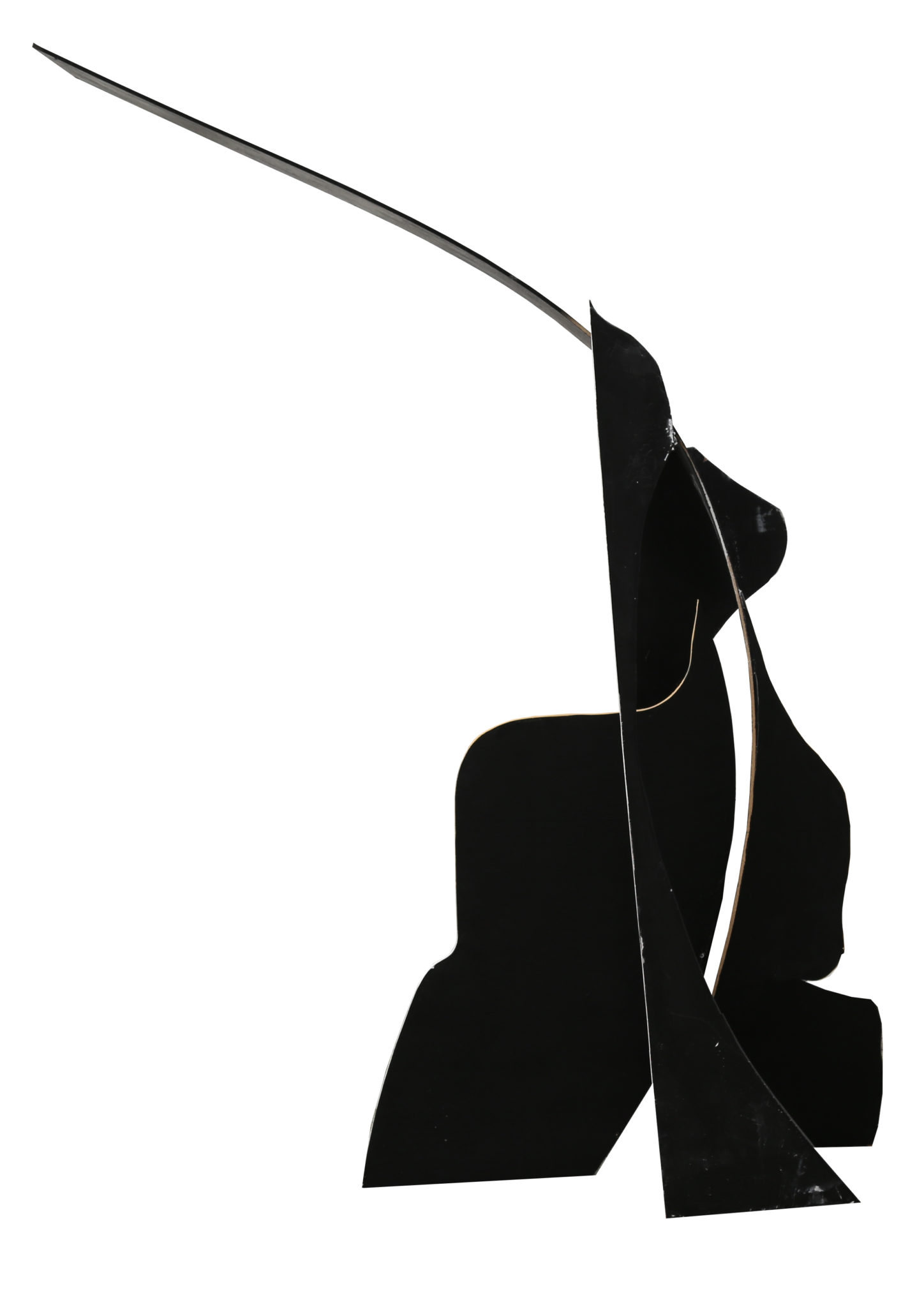

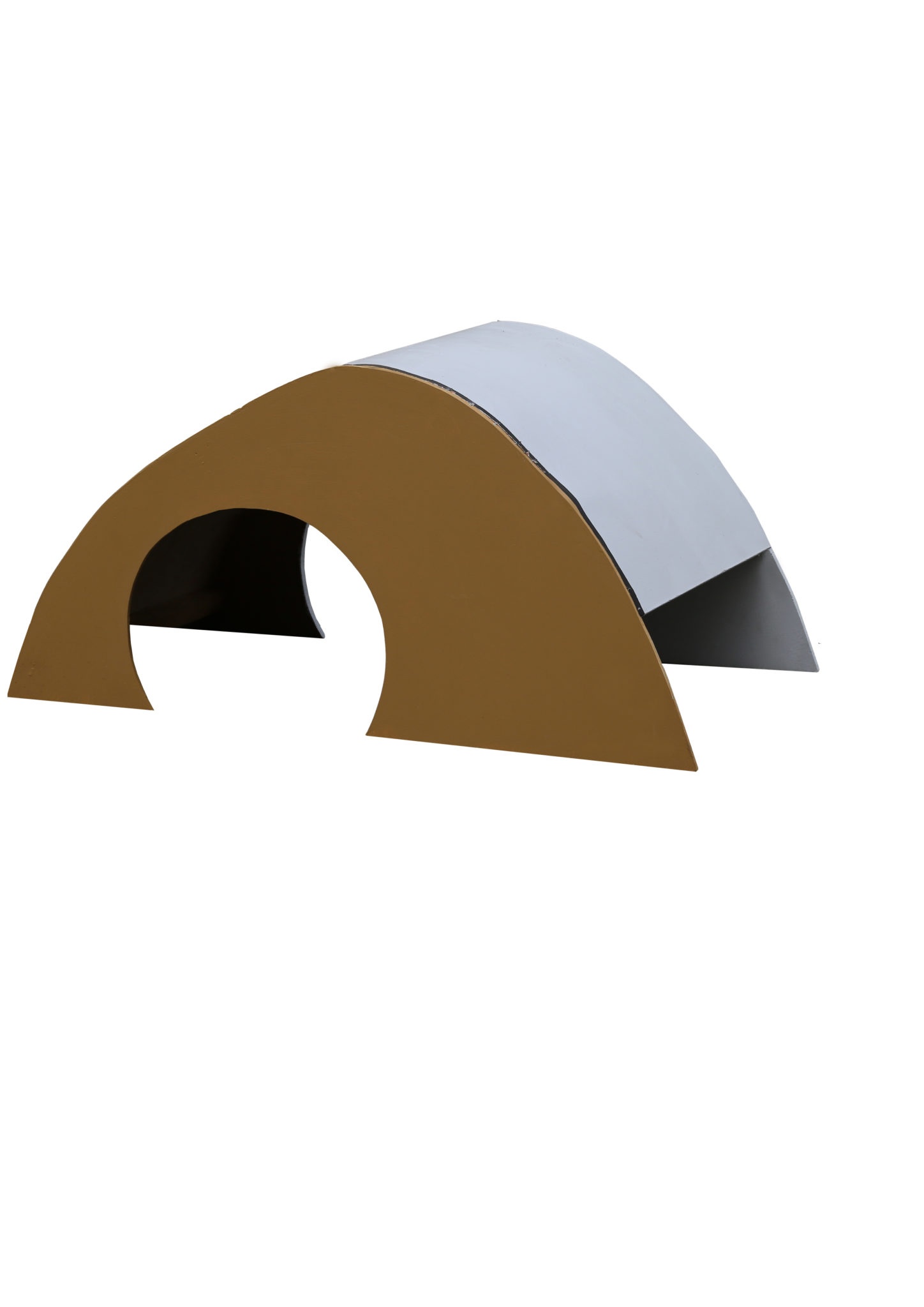

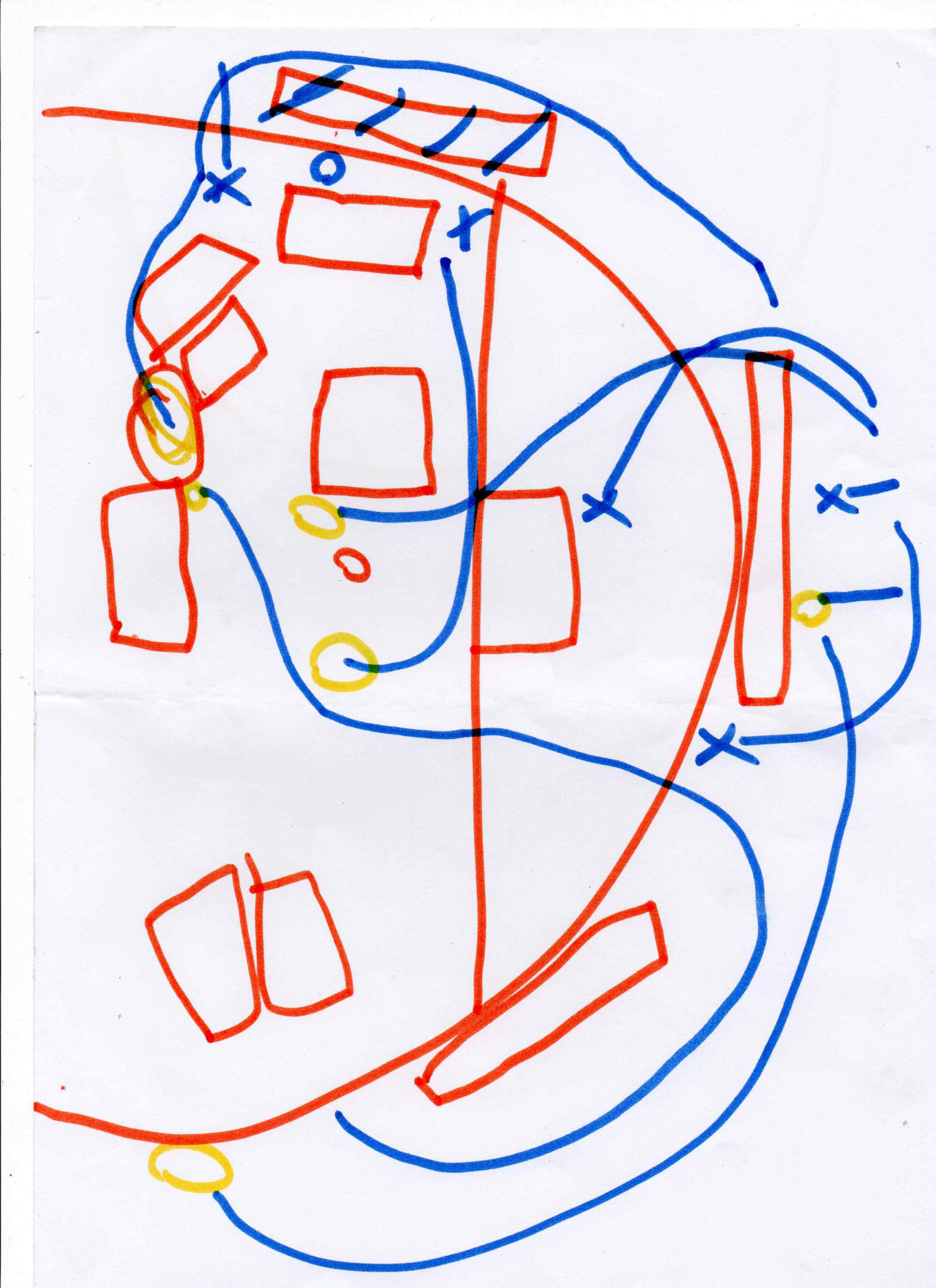

The first version of the game was initiated in collaboration with an intermediate basketball team from the Montreal area. After a few months of practice and experimentation we set the following rule : in reaction to a scored basket by a player, the artist is to place a volume (object, sculpture) on the court from where the shot was taken. The nature of the object (size, color, material) responds to the specific context of the exhibition space. In the game’s first iteration, the objects were collected in the exhibition place, and modified according to the safety standards imposed by the players like minimal height requirements and protection from sharp corners. These specifications gave the collected objects a sculptural dimension shaped by both players and artists.

Via this new rule, the gestural cues of artist and player become dependent on one another. The sculptures cum obstacles become scenario and instruction, which change the circumstances and goals of the game, focusing more on the development of new strategies. Visual and auditory signals by the referees introduce the rules into game play: if a basket is scored the artist must push a new sculpture onto the court from where it was shot, if an object is knocked down the responsible player is eliminated from play, if an object is bumped a team will lose a point. Perhaps the most difficult aspect of the game is that the objects on the court multiply quickly as both teams score points. This clutters the court like having 60 more players standing around. This provides new obstacles and barriers to consider for the artist who has to move sculptures onto the court, as well as for the players, who have the new opportunity to use the objects to their advantage while trying to negotiate them.

Every week practicing in the gymnasium our knowledge and methodology were tested, changing established positions of a each participant. Every player, referee and myself constantly challenged each other’s roles in a non-hierarchical way. This changed the way players would interact with each other negating the need for prescribed positions such as point guard. This established a heuristic learning method to which the game became a discussion and a negotiation space, everyone and everything on the court became actors and script writers, obliging the system of the game to change as it progresses using uncertainty as a springboard.

Developing this project is dependent on the hosting organization, city and largely the surrounding culture. It is is a project that I want to present in various cities confronting each culture according to their own rules of operation, reactions and interpretations of the game play. Each rendition will be unique. Working with a local basketball team will test the limits of each rendition of the game, as well as the system to which they are used to. Each context of the game will reveal ways to adapt it through observing reactions of the players, through discussion and practice. In each new city visited the players will play the last model of the game established in the previous place, the different contexts giving rise to new rules. Each version of the game will be recorded specific to a context as a form of cultural research.

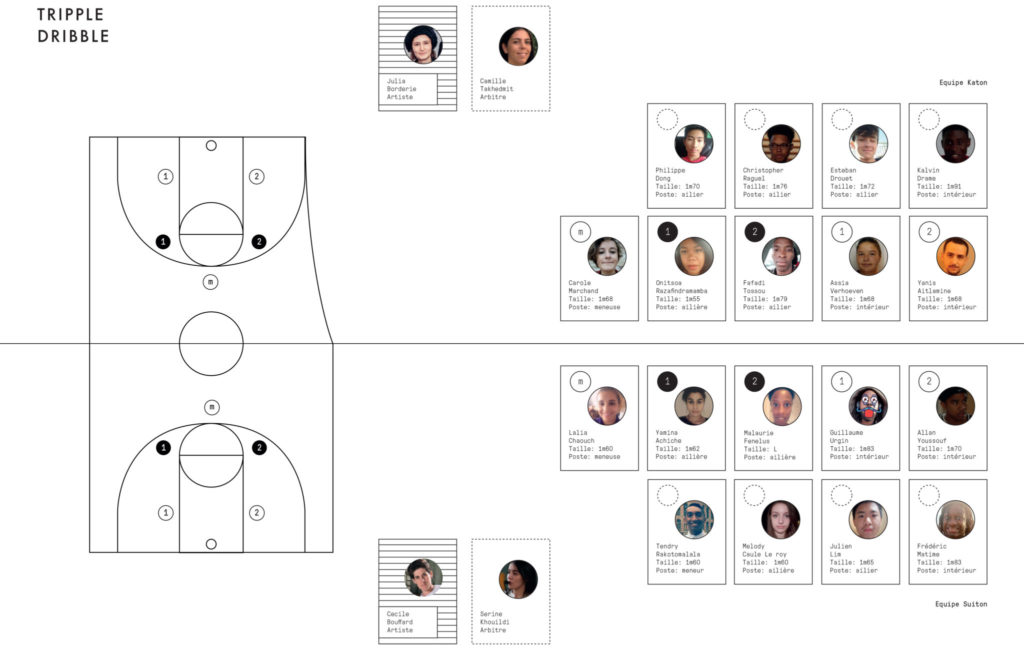

VAL DE MARNE

2018 – Collaborative project and performance | 130’’

In collaboration with Cécile Bouffard

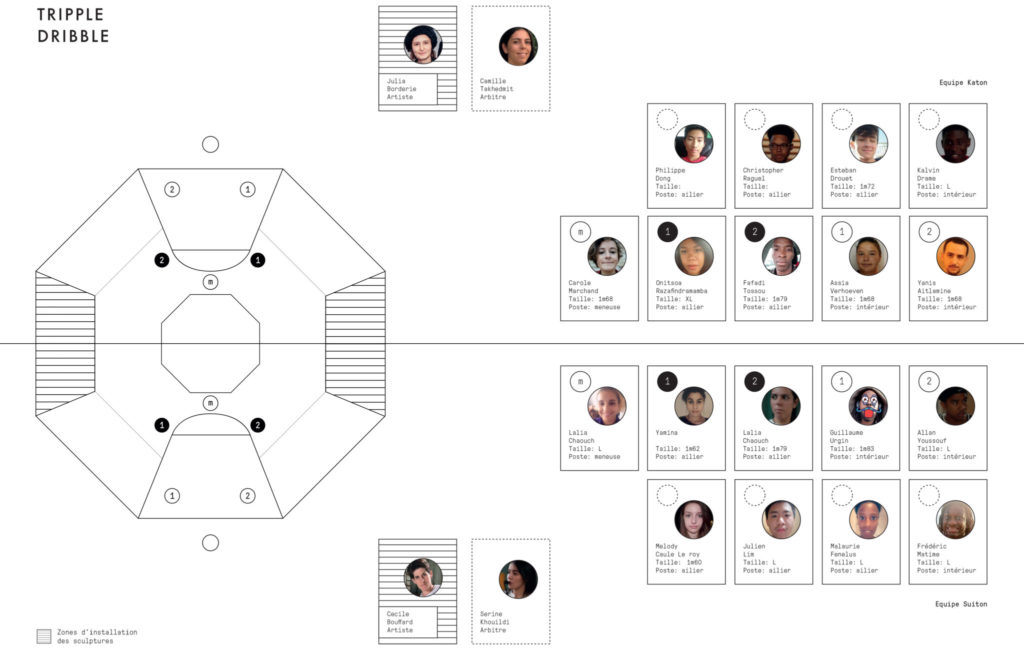

& the basketball players Allan Youssouf, Assia Verhoeven,Carole Marchand, Esteban Drouet, Fafadi Tossou, Frederic Matime, Julien Lim, Kalvine Drame, Lalia Chaouch, Malaurie Fenelus, Melody Caule le Roy, Miradi, Onitsoa Razafindramamba, Philippe Dong, Sacha Urgin, Yamina Achiche, Yanis Aitlamine ; and the referees Camille Takhedmit and Serine Khouildi, and the referees Jamil Rouissi, Christophe Denis and Erwan Abautret.

Projet producted by Jury des réalisations particulières du Val de Marne, galerie Fernand Léger gallery (Ivry-sur_seine), Jean-Collet gallery (Vitry-sur-Seine).

Tripple dribble focuses on Ivry-sur-Seine and Vitry-sur-Seine cities. The project was built in collaboration with players from the association École de la rue, the USI basketball club and Ivry’s women’s basketball club. Based on the rules that were stablished in Montreal we determined the types of sculptures and forms according to each shooting zone and to the characteristics of each player. These sculptures act as mediators between the players and challenge players of different skill to compete surrounding their new and unknown obstacles.

Place Voltaire, Ivry-sur-Seine

Dalle Robespierre, Vitry-sur-Seine

Galerie Jean-Collet

Tripple Dribble, 2018

Performance, 130’’

Tripple Dribble 2018

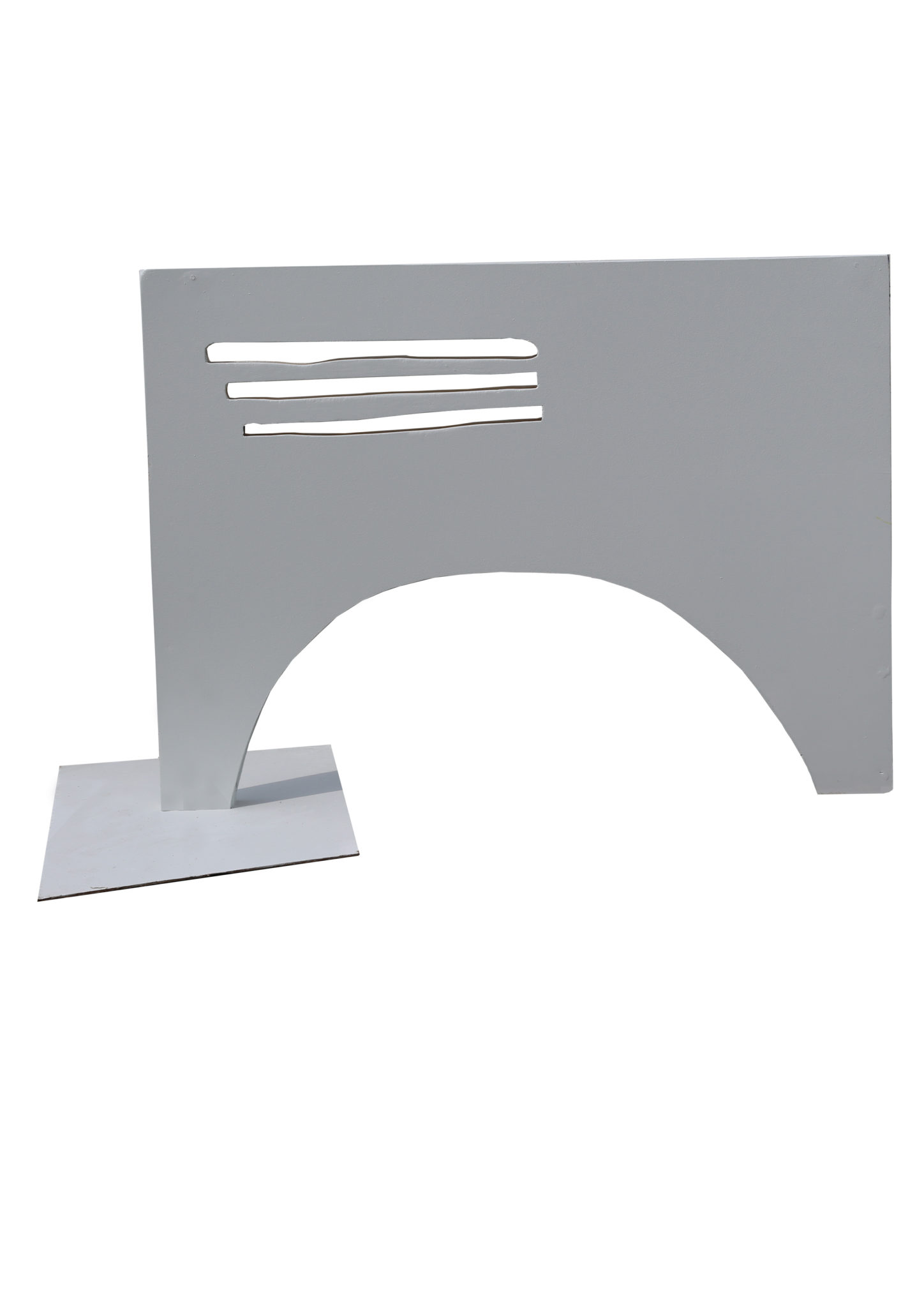

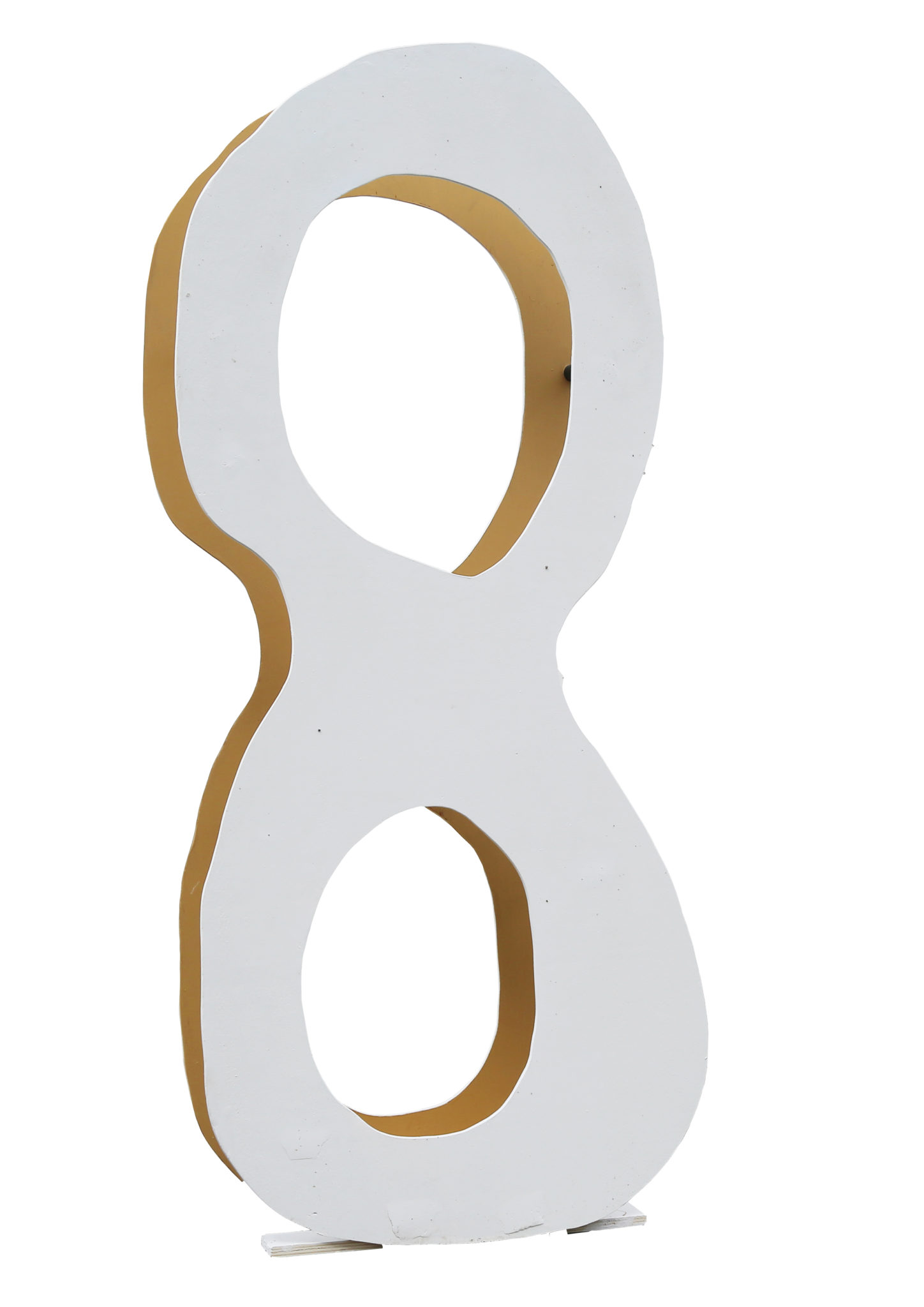

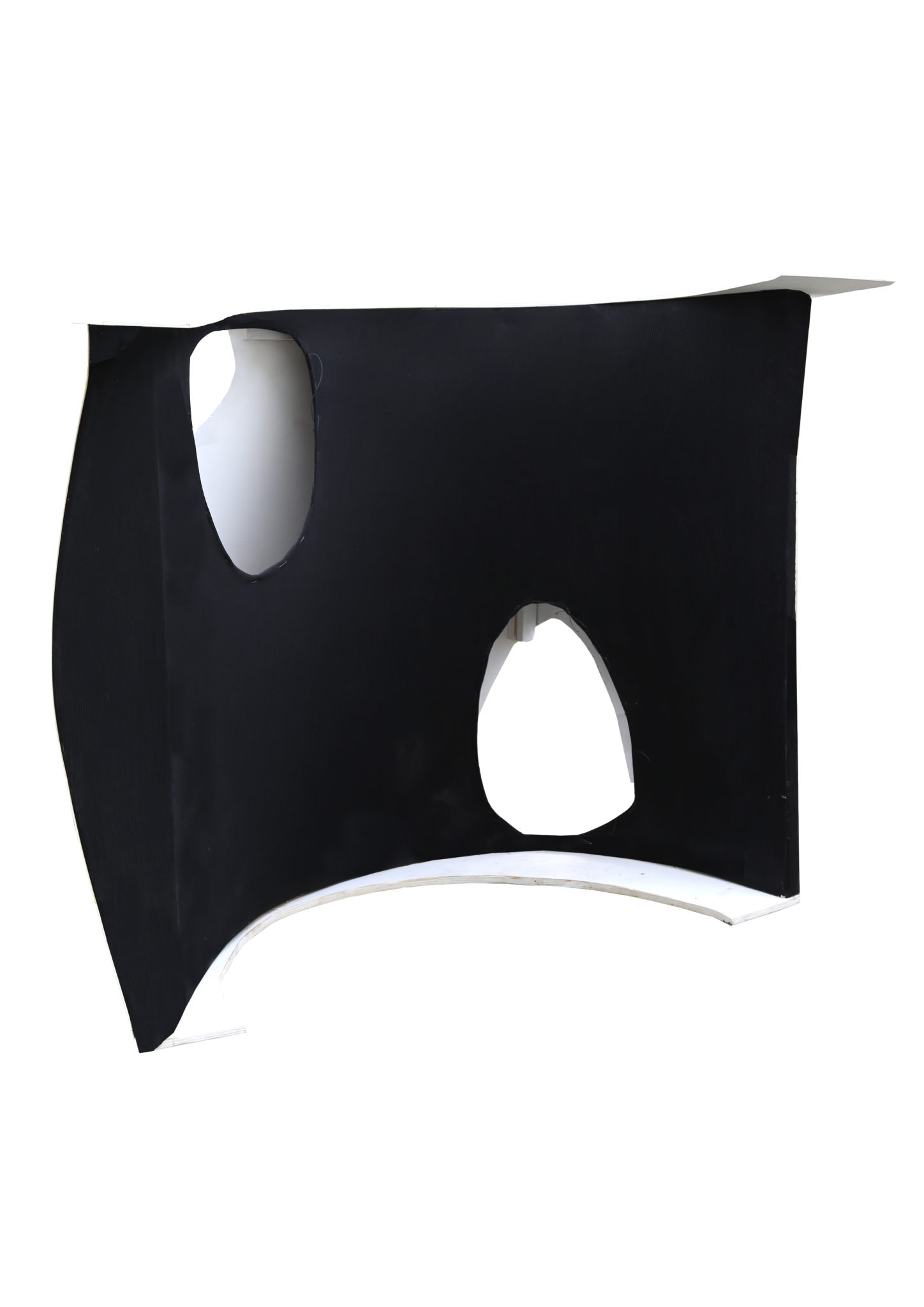

Sculpture, wood, painting, fabric

Variable formats

The Rules

Quarter time 1: a sculpture is placed at each basket marked at the place of the shot.

Quarter time 2: each player who scores a basket can move a volume on the court.

Half time: 5 minutes

Quarter time 3: Teams will play with the obstacles posed by the opposing team. If there are still sculptures to be placed, the first quarter time rule will apply.

Quarter time 4: For each basket scored, the player removes a sculpture from the attacking zone to the defending zone.

End of this quarter time: overtime if there is not at least 4 points difference. If this is the case on each basket scored, the scoring team has the right to remove one sculpture from the field.

The referees may impose obstacles on the pitch from the second half onwards.

Publication

Intervention : Jean-Marc Huitorel, critique d’art, Cécile Bouffard, artiste, Julia Borderie

Animation et Interview : Flore Di Sciullo

Chronique : Élodie Hervier

Réalisation : Lorna Bhi et Élodie Hervier

- Belle lutte au rebondi

Quand j’étais adolescente, au collège, le basket était un aimable chemin de croix. La balle était sale de tous les côtés et les maillots sentaient la sueur. Je n’ai jamais mis un panier ni empêché quoi que ce soit d’arriver, car d’ailleurs j’avais du mal à me rappeler à qui envoyer la balle si jamais je réussissais à l’avoir en main. Je regardais les marquages au sol comme des géoglyphes illisibles et mystérieux, ne distinguant pas ceux qui relevaient du terrain de foot, du terrain de handball ou de basket. J’étais la fille qui traîne mollement.

Devenir spectatrice, prendre des notes comme je le ferais dans une exposition ou un atelier d’artiste, c’est évidemment changer de point de vue.

Quelques remarques sur les personnages :

Les joueurs et les joueuses ont revêtu des maillots rouge et noir, et pour ma plus grande peine je n’ai à aucun moment réussi à savoir qui était avec qui. Les deux arbitres ont des cheveux d’un noir très brillant, avec des queues de cheval basses. Je cherche pendant un mois le tableau dont elles paraissent sorties, persuadée d’y avoir vu un Ingres alors qu’il s’agit de Fleur des champs (1845) de Louis Janmot, au Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. Peut-être s’amuseraient-elles d’être comparées, elles qui sont en constant mouvement sur le terrain, à cette muse aux bras indolents, noyée dans les fleurs sauvages. Elles gardent le sifflet à la bouche, imperturbables, et leurs gestes des mains – pour moi indéchiffrables – sont précis comme ceux d’une dentellière. Les commentateurs ne s’arrêtent jamais : c’est un all-over de voix, il ne faut laisser aucun blanc, le silence n’est pas une valeur en soi. J’aimerais parfois entendre davantage le chuintement des baskets sur le bitume comme des couinements de chatons affamés. Le dernier personnage, c’est le vent : il fait s’envoler les structures, il s’amuse à générer des larsens, il crée de petits tourbillons de feuilles mortes, de poussière et de pailles en plastique de Capri-Sun.

Un homme s’assied à côté de moi. Visiblement, il passait par là. Il jauge le terrain, les joueurs et les joueuses, jette de temps à autre un œil sur les résultats, puis se lance : « Non mais ! Dis donc ! C’est pas possible de garder autant la balle ! » assène-t-il en direction d’un joueur qu’il juge quelque peu égoïste. Il reste là sept ou dix minutes, peste encore sans animosité puis s’en va comme il était arrivé.

Le groupe de gamins du banc voisin sont d’excellents spectateurs : pour une raison inconnue, ils sont très vite acquis à la cause des rouges. Il y a du trémoussement dans l’air. Ils miment la douleur lorsque les noirs marquent, se prennent la tête dans les mains ou sautent de joie en hurlant lorsque les rouges reprennent la main, scandent des noms en chœur. Par charité, je décide de soutenir l’équipe noire.

Je note quelques phrases des commentateurs : il y a une « équipe plus axée sur le jeu demi-terrain », « un avaleur d’espace », « de la revanche dans l’air », « une belle lutte au rebondi ». Aux « jeunes gens », on recommande de « créer du mouvement ».

Du côté des sportifs, c’est plus laconique, mais surtout répétitif : « Tire ! Mais tire ! », « À nous, à nous ! » « Là, là ! », ou « Encore ! Encore ! ». Les bras sont levés, il ne faut pas se toucher, c’est toute une petite mécanique de l’empêchement qui se met en place.

On dit bien patinage artistique, pourrait-on inventer le basket-ball gracieux ?

Proposition d’arbitres : Marie Cool et Béatrice Balcou, pour la précision des gestes.

Proposition de commentateurs : Ben Vautier, pour le all-over ; Joseph Beuys, pour les punchlines ; Esther Ferrer, pour l’humour.

Proposition pour la conception des maillots : Bridget Riley, Yaacov Agam.

Proposition de nouveaux sports collectifs : match de volley dans Clara-Clara de Richard Serra, rugby avec Tête de muse endormie de Constantin Brancusi, hockey sur glace avec des Giacometti.

Je souhaite vraiment m’excuser. Au terme du match je ne savais pas qui avait gagné.

Camille Paulhan